Uncover Me: The Secret Story I Finally Tell (Part 2 of 3)

Issue 2860— September 30, 2025

Every kid fears they’re not normal. I had proof.

Last week I wrote about the power of telling the unvarnished truth of one’s story to enable leaders to build trust and credibility. I shared one layer of my story of growing up in small Texas towns and the chronology of my early formative years.

Yet life is a many layered thing. It tends to stack masks on us.

And I have learned from my own experience that great leaders know themselves and show themselves. They don’t polish the mirror; they stand in it. Researcher and bestselling author Brené Brown would say that showing vulnerability—revealing those uncomfortable places inside that might be invisible to others—makes a more effective leader.

As she acknowledges, “Vulnerability…[is] having the courage to show up when you can’t control the outcome.”

What terrifies us isn’t the truth—it’s surrendering control of the script.

On the personal level, shame and fear of losing the love of friends and family are often at the root of consciously covering the true self. Sometimes there may be a well-founded fear of public ostracism or physical violence; the latter is especially relevant for young Black men.

Leaders hold responsibility for outcomes. Losing control over one’s professional narrative is a legitimate concern—it can feel like dropping the wheel of the ship.

So back to my story. Here’s the part I’ve avoided.

I was born in Temple. Temple, Texas, that is, where there was only a handful of Jewish families, and no synagogue, in the buckle of the Texas Bible Belt. I always thought the late Kinky Friedman should have written a Country and Western song called “There Was No Temple in Temple.”

We then moved to an even smaller town in West Texas. I was the only Jewish student in my high school. My immigrant grandmother who spent a great deal of time with us spoke with a thick Russian-Yiddish accent. My friends, who I so wanted to fit in with, asked frequently where she was from, as though their West Texas drawls weren’t also accents, but never mind.

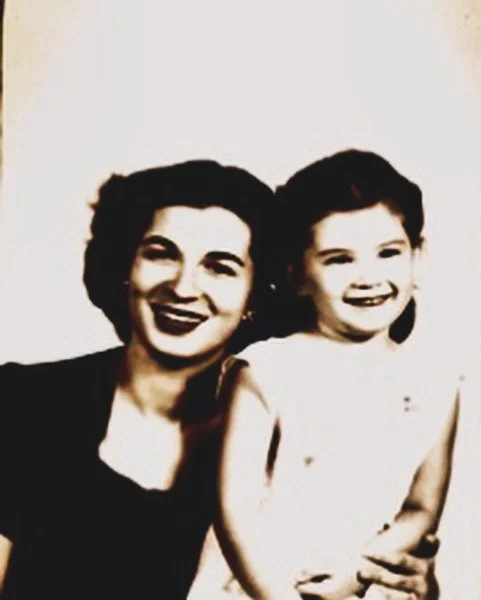

Me and my mother.

My parents, Florence and Max Feldt, owned a Western-wear factory—hard to miss in a farming town. I waited with trepidation for the inevitable the first question: “What church do you go to?” And the final hurdle was that my mother worked at the business while other moms were home and baked church-recipe cookies. When my grandmother was in town, at least she

redeemed me by making European fried cookies with powdered sugar that my friends coveted for after school treats.

So I always felt like an outsider. As kind as people usually were, they never let me forget that I was different—an “other.” My parents were non-observant and though they usually belonged to a synagogue in the nearest town an hour’s drive away, we also had Christmas trees and celebrated all the holiday trappings. I was an adult before I learned the Jewish Sabbath is on Saturday.

Still, despite taking on the feathers of the birds we lived among, we were seen as so different that I once received a letter addressed only “To the Eldest Daughter of Big Max, Stamford, Texas.”

My first actual brush with antisemitism was mild compared to many experiences people are having today. A fellow camper at Kickapoo Camp one summer informed me that the reason another camper’s clothes had mildewed in her laundry bag was because she was Jewish. Shocked, I said, “I’m Jewish, and my clothes are perfectly fine.” Then she looked shocked. I ran away—I didn’t know what else to say and the exchange with a girl I thought was a friend had cut deeply.

At that time, it was not unusual for Jews to be excluded from certain jobs and clubs; universities limited or excluded Jewish students, and a popular movie a decade earlier (Gentleman’s Agreement) had exposed how people with so-called Jewish names were discriminated against, from “restricted” communities where Jews couldn’t buy homes to being denied hotel reservations.

Like most young people, I wanted nothing more than to fit in. I was an expert at covering. “Covering” is a psychological concept that describes suppressing, altering, or muting aspects of one's true self to conform to perceived social or professional norms. The intent to avoid negative judgments, to fit in, maybe to avoid some kind of punishment. Gay people in the closet, for example.

Covering creates layers designed to enable us to fit in. They design the self-protective masks we wear.

I covered myself in small ways and large, hoping to belong. I yearned to be class favorite (and achieved it)—as if that title would stamp me worthy.

I learned to cook and sew because that’s what girls were supposed to do. I tried so hard to convince myself the domestic life akin to today’s “tradwives” was what I wanted because I had been acculturated to think it was what I wanted.

It took many years and hard experiences to realize I had not chosen my life’s path from my own intention. I had been covering.

“Covering” is the quiet costume change—muting parts of ourselves to pass the vibe check of a room.

Covering may come from hand-me-down beliefs that our parents or our culture instilled in us before we had the maturity to evaluate how we felt and what we believed. Millions of professional women, and both men and women of color, often cover today, while working in institutions designed by (largely white) men for men like themselves.

Covering costs a soul tax—with compound interest.

There is a phrase a poet once wrote: “You will be found out if you sing a song that is not your own.”

Having the courage to know and show yourself is the ultimate gift of integrity. And for me, precisely because of the years of hard excavation through the muck of socialization, integrity is the most important of all virtues. Though the path is arduous, the destination gives the oxygen necessary for survival.

That’s why “Uncover Yourself” is the first of the nine leadership intentioning tools in my book, Intentioning: Sex, Power, Pandemics, and How Women Will Take the Lead for (Everyone’s) Good.

Where are you still dimming your light? What mask could you take off this week? What would you dare—once you stop hiding?

Reply with the one mask you’ll drop this week—or email me at takethelead@taketheleadwomen.com.

Next week, I’ll share how I came to be incredibly grateful for the experience of being “other”—and how events today are presenting new layers for new generations to plumb.

GLORIA FELDT is the Co-founder and President of Take The Lead, a motivational speaker, and a global expert in women’s leadership development and DEI for individuals and companies that want to build gender balance. She is a bestselling author of five books, most recently Intentioning: Sex, Power, Pandemics, and How Women Will Take The Lead for (Everyone’s) Good. Honored as Forbes 50 Over 50, and Former President of Planned Parenthood Federation of America, she is a frequent media commentator. Learn more at www.gloriafeldt.com and www.taketheleadwomen.com. Find her @GloriaFeldt on all social media.